How dows OSGi handle version ?

In OSGi you define your dependencies using headers in the Manifest. There are several ways to define dependencies (Import-Package, Require-Bundle, etc...). One way to constrain a dependency is to use version. A version in OSGi is defined as Major.Minor.Micro.qualifer.

Example of versions:

1 1.0 2.4.5.ABC_DEF

- Major, Minor and Micro must be numbers. The qualifier is a string (with some constraints) and is not interpreted as a number (check the javadoc for the details).OSGi does not attach any more meaning to the numbers and it is up to the user to manage the numbers the way they want.

- When defining a dependency, you can use a version or a version range.

version=1.0.0

does not mean that you depend on version 1.0.0, but it means that you depend on 1.0.0+ meaning anything greater than (or equal to) 1.0.0 will match!

If you really want to express that you depend on 1.0.0 and nothing else, it is expressed this way:

version=[1.0.0,1.0.0]

Example of ranges:

version=1 => means v >= 1.0.0 version=[1.1.0,2) => means 1.1.0 <= v < 2.0.0 version=(1,2] => means 1.0.0 < v <= 2.0.0

Versionning convention

As mentionned previously, OSGi does not attach any meaning to the various components of a version. Here is the convention that seems to have been adopted by some open source projects.

- The Major number represents a major version: it is assumed that there is no backward compatibility between 2 different versions of the same bundle where the major number is different. Usually it means that APIs have changed in a non compatible way. (It would for example be the case if java serialized objects have been changed in a way that their serial version ID is different).

- The Minor number represents a version which contains changes that are backward compatible. A backward compatible change is for example, the addition of a method to an interface or new classes and objects not present in a previous version.

- The Micro number represents a version which is also backward compatible but does not contain any api enhancements. It is usually used for bug fixes and minor improvements.

- The qualifier is a string and is being used for various purposes depending on the project.

Upgrading version

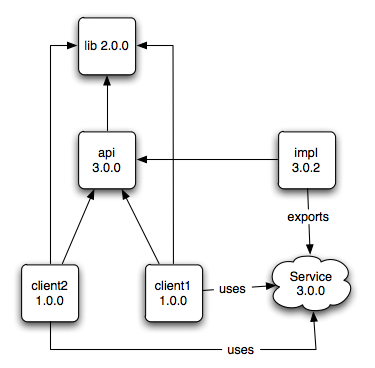

Let's take the following example:

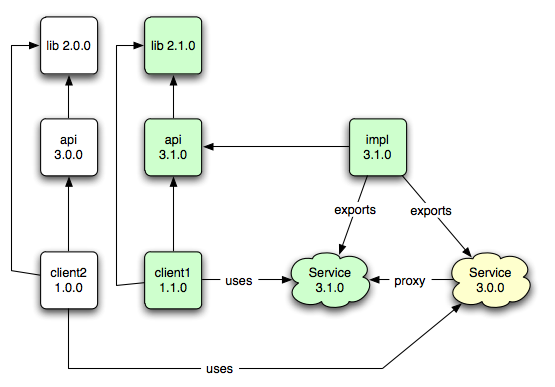

There is a service which is exposed as a java interface. This java interface resides in the bundle api-3.0.0. A service does not really have a version but since it uses this api it is fair to say that the version of the service is 3.0.0. The bundle impl-3.0.2 provides the implementation of the service and exports it to the OSGi registry. There are 2 clients of the service (client1 and client2). They both depend on the api. Also there is another external bundle (called lib-2.0.0) which happens to be used by both clients both directly (in their code) and indirectly because the api exposes some objects from this library in the api.

Service API (3.0.0) ------------------- void f(FromLib200 param1);

Upgrade scenario

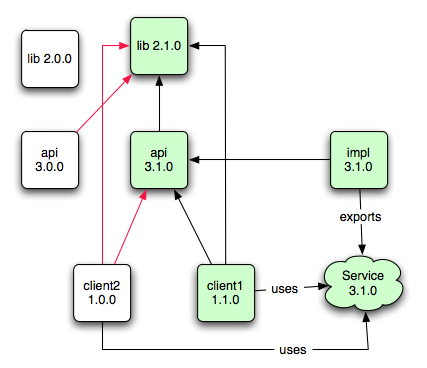

Lets now assume we enhance the service in a backward compatible way by offering a new api (new method on the java interface).

Service API (3.1.0) ------------------- void f(FromLib200 param1); void g(FromLib210 param1);

The new service API actually uses a new class which was not defined in the previous version of lib, thus requiring a new lib-2.1.0. We then assume that client1 uses this new enhanced api while client2 is left unchanged. Of course there needs to be a new implementation for this new api.

Upgrade results with minimal version lockdown

In this first case, we are assuming that we lockdown version only for protecting against incompatible changes. In other words we use ranges like this, locking down only on the major version number:

client1: api;version=[3.1.0,4),lib;version=[2.1.0,3) client2: api;version=[3.0.0,4),lib;version=[2.0.0,3) api-3.0.0: lib;version=[2.0.0,3) api-3.1.0: lib;version=[2.1.0,3)

Here is the result:

Although client1 has not been updated, it is going to start using the new service. Since the new service is backward compatible it is not really an issue per se. What is an issue though is that it is also going to start using lib-2.1.0. Why is it an issue exactly ? In a very dynamic production environment (like LinkedIn's), this scenario is very frequent. The danger comes from the fact that by simply deploying a new version of a service, it ends up affecting a client in a way that has most likely not being tested.

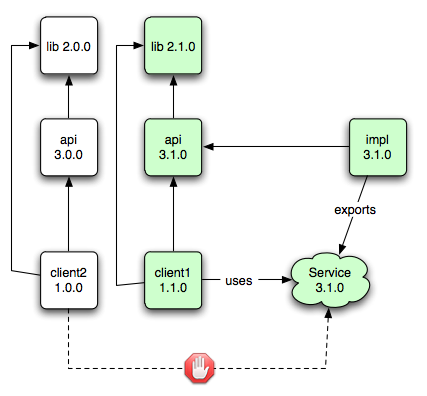

Upgrade results with maximal version lockdown

In this second case, we are assuming that we lockdown the version entirely. In other words we use ranges like this, locking down major, minor and micro:

client1: api;version=[3.1.0,3.1.1),lib;version=[2.1.0,2.1.1) client2: api;version=[3.0.0,3.0.1),lib;version=[2.0.0,2.0.1) api-3.0.0: lib;version=[2.0.0,2.0.1) api-3.1.0: lib;version=[2.1.0,2.1.1)

Here is the result:

Is there a solution then ?

As we mentionned previously, client2 should be able to talk to the new service because it is backward compatible. The only reason it cannot talk to it is due to class loading. If we were in separate containers we would not really have this problem (we would use spring rpc which does java serialization). So the idea is to replicate what happens when we are remote:

We can deploy a service which uses service 3.0.0 api and proxies all the call to the real service (we know that due to backward compatibility, the API of Service 3.0.0 is a subset of 3.1.0 so we should be able to proxy all calls). Due to class loading issues, the calls must go through java serialization (exactly like what would happen if it was remote...): in other words, we serialize all parameters with the class loader which loaded Service 3.0.0 and we deserialize with the one which loaded Service 3.1.0 (and vice versa for the return value/exceptions).